Introduction: The Historian’s Long View

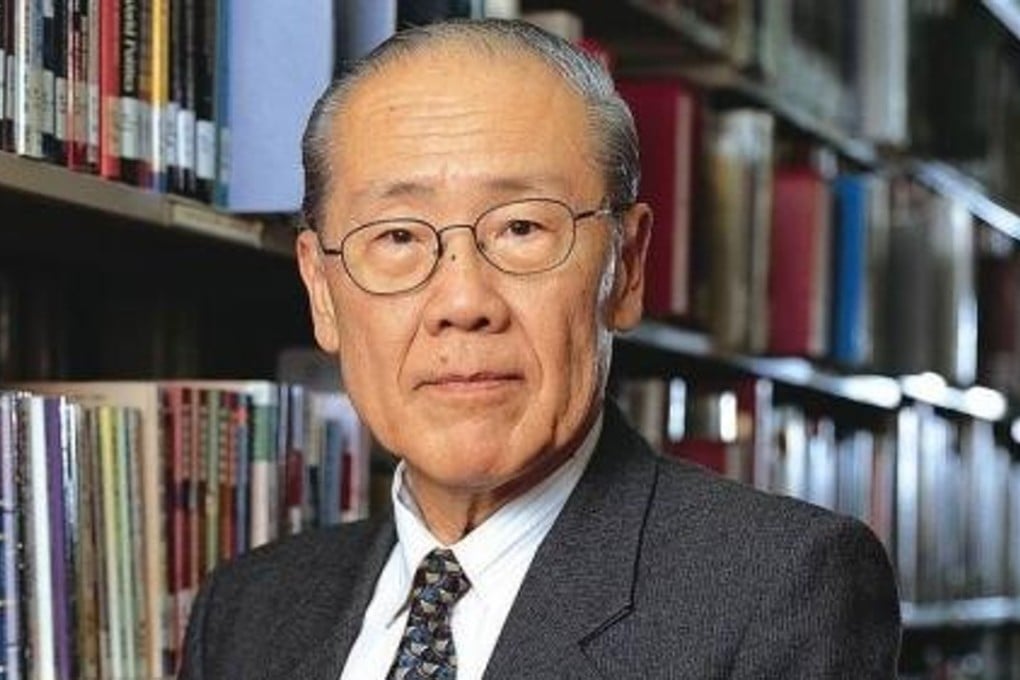

Professor Wang Gungwu’s insights into Chinese history, culture, and contemporary geopolitics offer a profound analytical framework for understanding the current US-China trade tensions. His distinction between “culture” and “civilisation,” combined with his understanding of China’s historical DNA and strategic mindset, provides crucial context for interpreting the ongoing trade conflicts that have intensified under Trump’s second presidency.

The Culture-Civilisation Paradigm and Trade Relations

Theoretical Framework

Wang’s fundamental distinction between culture (national) and civilisation (a borderless human achievement) illuminates a critical misunderstanding in current US-China relations. The trade war often conflates economic competition with civilizational clash, when in fact it represents a collision between two distinct national cultures attempting to assert dominance.

Culture as National Identity:

- China’s national culture under Xi Jinping draws from Confucian and Legalist traditions

- The US national culture, particularly under Trump, has shifted from post-Cold War idealism to pragmatic power politics

- Both nations are developing economic policies that align with their respective cultural narratives of strength and sovereignty.

Civilizational Appreciation vs. National Competition: Wang’s framework suggests that Americans can appreciate Chinese technological innovations (such as high-speed rail or renewable energy) and that Chinese can value the American entrepreneurial spirit, even while their governments engage in economic competition. The tragedy of the current moment is that trade war rhetoric prevents this civilizational appreciation.

Current Trade War Context

The 2025 trade tensions reflect this culture-civilisation confusion. Recent developments show China retaliating with 10-15% tariffs on US agricultural products after Trump imposed new tariffs, while Trump has implemented a 10% blanket tariff on all Chinese imports. These actions represent national cultural assertions rather than civilizational engagement.

China’s Historical DNA and Strategic Patience

The Non-Expansionist Thesis

Wang’s argument that China’s historical DNA is non-expansionist provides crucial context for understanding Chinese behavior in the trade war. His reference to the Ming Dynasty’s restrictions on overseas trade, aimed at keeping people within the continental empire, suggests a fundamental difference in strategic thinking from Western maritime powers.

Implications for Trade Policy:

- China’s Belt and Road Initiative, often seen as expansionist, may actually reflect this inward-pulling tendency, creating a continental network that draws trade toward China rather than projecting power outward

- Chinese negotiating strategy in trade talks reflects this patient, defensive mindset rather than aggressive expansion

- The focus on domestic consumption and technological self-reliance (dual circulation strategy) aligns with historical patterns of continental consolidation.

The Multipolar World Vision

Wang’s observation that China prefers a multipolar rather than bipolar world order has profound implications for current trade negotiations. Recent reports suggest US and Chinese negotiators have reached a framework for a trade truce, though details remain undisclosed. This development supports Wang’s thesis that China seeks “room to maneuver” rather than direct confrontation.

Strategic Implications:

- China’s trade policy aims to create multiple dependencies rather than bilateral dominance.

- The emphasis on ASEAN, African, and European partnerships reflects multipolar thinking.

- Trade war escalation contradicts China’s preferred strategic environment

The South China Sea Parallel in the Economic Sphere

Historical Context and Current Application

Wang’s analysis of the South China Sea, noting that the nine-dash line was drawn by the Kuomintang in 1947 with Western approval, offers a template for understanding Chinese positions on economic sovereignty. Just as China’s maritime assertiveness stems from historical memories of foreign bases being used against it, Chinese economic defensiveness reflects similar historical trauma.

Economic Sovereignty Parallels:

- Chinese restrictions on foreign technology companies mirror concerns about strategic economic bases

- The emphasis on technological self-reliance reflects the same defensive mindset Wang describes regarding maritime security.

- Trade war responses tend to follow a pattern of reactive rather than proactive policy.

The “Bases” Metaphor in Economic Terms

Wang’s insight about European powers using Southeast Asian bases to attack China translates to contemporary economic anxieties:

- US technology companies (Google, Facebook, Microsoft) are seen as potential economic “bases” for influence

- Chinese restrictions on foreign investment in strategic sectors reflect historical wariness

- China’s leverage through rare earths control represents a defensive use of economic “bases”

The Convergence Thesis: America Becoming More Like China

Ideological Shifts

Wang’s provocative observation that “the US is starting to become more like China” under Trump provides the most insightful lens for understanding current trade dynamics. This convergence manifests in several ways:

Policy Convergence:

- Both nations now prioritise economic nationalism over multilateral trade liberalisation

- Industrial policy has returned to prominence in both countries

- State intervention in markets has increased on both sides

Rhetorical Convergence:

- Both leaders emphasise national greatness and sovereignty

- Economic competition framed in civilizational rather than purely commercial terms

- Protectionist measures justified through cultural/political rather than economic logic

Post-Democratic Idealism

Wang’s reference to Trump defeating the “democratic ideals represented by Bill Clinton and Barack Obama” explains why traditional trade negotiation frameworks have failed. The US no longer approaches trade as a vehicle for spreading democratic values, but as a tool for national power projection—much like China has always viewed it.

Singapore Model: Lessons for Trade Relations

Managing Plurality Without Domination

Wang’s admiration for Singapore’s constitutional approach to managing Chinese plurality offers a model for US-China economic relations. Singapore encourages local Chinese identities (Hokkien, Hakka) that maintain distance from mainland Chinese national culture while preserving civilizational connections.

Application to Trade Relations:

- Economic partnerships can maintain civilizational exchange while preserving national sovereignty

- Sector-specific agreements (like the recent rare earths negotiations) allow for cooperation without wholesale cultural submission

- The current trade deal framework awaiting Trump and Xi’s signatures could follow this model of limited, specific cooperation

Constitutional Consistency

Wang praises Singapore’s “constitutionally justified and consistent” approach to plurality. Current trade negotiations lack this constitutional framework—both nations are improvising based on immediate political needs rather than long-term structural principles.

Contemporary Trade War Analysis Through Wang’s Framework

The Mandate of Heaven in Economic Terms

Wang’s observation that Xi Jinping continues Confucian tradition by “protecting the weak against the strong” through anti-corruption campaigns has economic policy implications. Chinese trade negotiating positions often emphasize protecting domestic industries and workers from foreign competition—a economic version of the imperial responsibility to prevent excessive wealth concentration.

American Power Projection vs. Chinese Continental Thinking

The fundamental mismatch in the trade war stems from different conceptions of economic power:

American Approach (Maritime/Projective):

- Uses economic sanctions and tariffs as tools of global influence

- Expects trade agreements to project American values and systems globally

- Views economic partnerships as extensions of alliance systems

Chinese Approach (Continental/Defensive):

- Uses trade policy to strengthen domestic industrial base

- Seeks economic agreements that preserve policy autonomy

- Views economic partnerships as mutually beneficial without systemic change

The Efficiency vs. Stability Trade-off

Current analysis suggests the tariff escalation could “distort production patterns and drive a sharp reconfiguration of global value chains, resulting in a less efficient and more opaque” system. This efficiency loss reflects Wang’s broader point about the costs of treating economic competition as civilizational conflict.

Wang’s framework suggests that both nations are sacrificing economic efficiency for cultural/political stability—a trade-off that makes sense from his long historical perspective but creates short-term economic costs.

Implications for Future US-China Relations

Beyond the Trade War

Wang’s insights suggest that current trade tensions represent a transitional phase rather than a permanent state. His observation that “working together doesn’t seem feasible” while “working against each other is dangerous” points toward an eventual modus vivendi based on managed competition rather than integration or conflict.

The Multipolar Economic Order

Recent analysis indicates that “China’s control over critical supply chains” is increasing while “America’s position is weakening over time”. This development supports Wang’s multipolar thesis—economic power is becoming more distributed, making bilateral trade wars less effective.

Cultural Understanding vs. Economic Competition

Wang’s longevity secret—continuing to ask “What will happen?” while finding uncertainty both “terrifying” and “interesting”—offers a model for approaching US-China relations. The current trade war reflects a failure of imagination about alternative approaches to economic competition that preserve both national cultures while enabling civilizational exchange.

Conclusion: Historical Wisdom for Contemporary Challenges

Wang Gungwu’s analysis provides essential historical context for understanding why traditional approaches to US-China trade relations have failed and what alternatives might work. His insights suggest that sustainable economic relations require:

- Distinguishing between cultural competition and civilizational cooperation

- Recognizing China’s defensive rather than expansionist strategic DNA

- Accepting the US transformation from idealistic to pragmatic power politics

- Developing constitutional frameworks for managing economic plurality

- Embracing multipolarity as a path to sustainable competition

The current trade war represents a failure to apply these historical lessons. Wang’s framework suggests that eventual resolution will require both nations to develop new approaches that honor their distinct cultural imperatives while enabling continued civilizational exchange—much as Singapore has managed to do in its unique context.

At 94, Wang continues to demonstrate that historical wisdom remains essential for navigating contemporary challenges. His ability to find uncertainty both terrifying and interesting offers a model for approaching US-China relations with neither naive optimism nor paralyzing pessimism, but with the kind of patient, informed curiosity that has characterised the best historical analysis across centuries.

Introduction: Two Visions of Civilizational Interaction

The relationship between Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” thesis and Wang Gungwu’s civilizational framework represents one of the most significant intellectual debates in contemporary international relations theory. While both scholars acknowledge the centrality of civilizations in shaping global politics, their approaches differ fundamentally: Huntington predicts inevitable conflict along civilizational fault lines, while Wang offers a more nuanced model of civilizational coexistence and mutual influence.

Huntington’s Civilizational Determinism

The Core Thesis

Samuel Huntington’s influential 1993 theory posited that the primary axis of conflict in the future will be along cultural lines, with the concept of different civilizations becoming increasingly useful in analyzing the potential for conflict. His central argument was that people’s cultural and religious identities will be the primary source of conflict in the post-Cold War world, with future wars fought not between countries, but between cultures.

Huntington’s framework emerged from the observation that with the end of the Cold War, countries stopped defining themselves by the ideologies they aligned with, leading to a resurgence of cultural and religious identity as organizing principles for international politics.

The Conflict Paradigm

Huntington’s thesis rests on several key assumptions:

- Civilizations are monolithic and internally coherent

- Civilizational differences are irreconcilable and lead to inevitable conflict

- The post-Cold War world would be characterized by civilizational blocs in opposition

- Cultural identity trumps other forms of political organization

His framework identifies multiple civilizations but focuses particularly on potential conflicts between Western, Islamic, and Confucian (Chinese) civilizations.

Wang Gungwu’s Civilizational Pluralism

The Four-Civilization Framework

Wang Gungwu explicitly acknowledges Huntington’s influence while developing a more sophisticated alternative. The interview reveals that Wang “takes his cue from American political scientist Samuel Huntington” but reaches fundamentally different conclusions. Wang identifies four primary civilizations: the Indic, Sinic, Islamic, and European Christian civilizations, later adding what he terms the “Neo-modern” or Global Maritime civilization.

Beyond Clash: The Coexistence Model

Wang’s most significant departure from Huntington lies in his emphasis on civilizational synthesis rather than conflict. His analysis of Southeast Asia demonstrates how societies have been “proud bearers of the ancient civilisations – in one combination or another” while having “the local genius of not adopting any one of those civilisations holistically or singularly, but selecting elements” from multiple traditions.

This selective appropriation challenges Huntington’s assumption of civilizational purity and inevitable conflict.

The Culture-Civilization Distinction: Wang’s Key Innovation

Theoretical Sophistication

Wang’s crucial contribution lies in his distinction between “culture” (national) and “civilization” (borderless human achievement). This framework offers a more nuanced understanding than Huntington’s approach, which often conflates the two concepts.

Wang’s Framework:

- Culture: Tied to nation-states and political identity

- Civilization: Transcends political boundaries and represents universal human achievements

Huntington’s Framework:

- Treats culture and civilization as largely synonymous

- Links both primarily to religious and ethnic identity

- Assumes political organization follows civilizational lines

Practical Applications

Wang’s distinction explains phenomena that Huntington’s model cannot adequately address:

- How individuals can appreciate Shakespeare while not identifying with Western political systems

- Why overseas Chinese can maintain civilizational connections while developing distinct national cultures

- How Singapore successfully manages multiple civilizational influences within a single political framework

China as the Test Case

Huntington’s Chinese Challenge

Huntington viewed China as representing “the greatest challenge to Western modernity,” predicting inevitable conflict between Confucian and Western civilizations. His framework suggested that China’s rise would necessarily create a bipolar confrontation with the West.

Wang’s Alternative Reading

Wang’s analysis offers a fundamentally different interpretation of China’s role:

Non-Expansionist DNA: Wang argues that China’s historical pattern is continental consolidation rather than maritime expansion, contradicting Huntington’s assumption of inevitable Chinese expansionism.

Multipolar Preference: Rather than seeking bipolar confrontation with the West, Wang suggests China prefers a multipolar world that provides “room to maneuver.”

Civilizational Confidence: Wang sees China’s assertiveness as reflecting civilizational confidence rather than cultural imperialism, allowing for coexistence rather than requiring dominance.

Southeast Asia: Laboratory for Civilizational Interaction

Huntington’s Blind Spot

Huntington’s framework struggles to explain Southeast Asian societies, which don’t fit neatly into his civilizational categories. His model would predict either fragmentation along civilizational lines or dominance by one civilisation over others.

Wang’s Synthesis Model

Wang’s analysis of Southeast Asia, particularly Singapore, demonstrates successful civilizational synthesis:

Multiple Civilizational Inheritance: Southeast Asian societies have been shaped by “the influence of four civilisations – the Indic, Sinic, Islamic and European-Christian” without requiring the dominance of any single tradition.

Constitutional Pluralism: Singapore’s success in managing Chinese plurality while maintaining distance from mainland Chinese national culture exemplifies how civilizational appreciation can coexist with a distinct national identity.

Local Genius: The concept of “local genius” in selecting elements from multiple civilisations while maintaining a coherent national identity directly challenges Huntington’s assumption of civilizational incompatibility.

Contemporary Relevance: Trade Wars and Civilizational Misunderstanding

Huntington’s Influence on Current Conflicts

Current US-China tensions often reflect Huntingtonian thinking, treating economic competition as a form of civilizational conflict. This approach:

- Frames trade disputes as zero-sum civilizational struggles

- Prevents appreciation of mutual civilizational achievements

- Creates self-fulfilling prophecies of conflict

Wang’s Alternative Path

Wang’s framework suggests that current tensions reflect a failure to distinguish between legitimate cultural competition and unnecessary civilizational conflict:

Civilizational Appreciation: Americans can value Chinese technological innovations while competing economically with Chinese national policies.

Cultural Competition: Nations can assert their distinct approaches to governance and economics without rejecting the achievements of other civilisations.

Multipolar Cooperation: A world of multiple civilizational influences allows for diverse approaches to modernity without requiring uniformity or dominance.

Theoretical Implications: Beyond the Clash Paradigm

Huntington’s Limitations

Wang’s work reveals several critical limitations in Huntington’s approach:

Static Conception: Huntington treats civilisations as fixed entities rather than dynamic, evolving traditions capable of synthesis and mutual influence.

Binary Logic: The clash paradigm assumes civilizational interaction must be either assimilation or conflict, missing possibilities for creative synthesis.

Political Reductionism: Huntington reduces complex civilizational interactions to political and military competition, overlooking cultural, intellectual, and artistic exchange.

Wang’s Dynamic Model

Wang’s framework offers several advantages:

Evolutionary Understanding: Civilizations are seen as living traditions capable of growth, adaptation, and mutual enrichment.

Synthesis Possibilities: The model accommodates creative combinations of civilizational elements without requiring purity or dominance.

Multilevel Analysis: Wang distinguishes between civilizational appreciation, cultural identity, and political organization, allowing for more nuanced understanding of international relations.

The Singapore Synthesis: A Model for Global Relations

Beyond Huntington’s Predictions

Singapore’s success directly contradicts Huntington’s predictions. According to the clash thesis, a society combining Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Western influences should experience constant internal conflict and eventual fragmentation.

Wang’s Explanatory Power

Wang’s framework explains Singapore’s success through several mechanisms:

Constitutional Pluralism: Legal and institutional frameworks that accommodate multiple civilizational influences without requiring assimilation.

Cultural Differentiation: Encouraging local Chinese dialects and clan associations that maintain civilizational connections while distinguishing national from civilizational identity.

Selective Appropriation: The “local genius” of choosing beneficial elements from multiple civilizations while maintaining social coherence.

Historical Wisdom vs. Contemporary Anxiety

Huntington’s Post-Cold War Anxiety

Huntington’s thesis emerged from legitimate concerns about post-Cold War instability but projected Western anxieties about cultural change onto a global framework that predicted inevitable conflict.

Wang’s Historical Perspective

Wang’s 94-year perspective offers historical wisdom that transcends contemporary anxieties:

Civilizational Resilience: His observation that “China is the only major civilization that has fallen down four times and stood up again each time” suggests civilizational durability rather than fragility.

Adaptive Capacity: Historical examples demonstrate civilizations’ ability to adapt, synthesize, and coexist rather than inevitably clash.

Long-Term Perspective: Wang’s approach encourages patience and understanding rather than fear and confrontation.

Implications for Contemporary International Relations

Moving Beyond the Clash Paradigm

Wang’s work suggests several principles for international relations that transcend Huntington’s conflict model:

Civilizational Humility: Recognition that no single civilization has a monopoly on valuable insights or achievements.

Synthesis Opportunities: Active seeking of ways to combine civilizational strengths rather than defending civilizational purity.

Constitutional Innovation: Development of legal and institutional frameworks that accommodate civilizational diversity within coherent political systems.

Practical Applications

Wang’s framework offers guidance for contemporary challenges:

US-China Relations: Focus on managing cultural competition while enabling civilizational exchange and mutual learning.

Global Governance: Design international institutions that reflect civilizational diversity rather than imposing single models.

Regional Integration: Learn from Southeast Asian examples of successful civilizational synthesis.

Conclusion: From Inevitable Clash to Possible Coexistence

The intellectual dialogue between Huntington’s clash thesis and Wang Gungwu’s civilizational pluralism represents more than academic debate—it offers fundamentally different paths for global development. Where Huntington saw inevitable conflict, Wang demonstrates possible coexistence. Where Huntington predicted civilizational dominance, Wang shows successful synthesis.

Wang’s 94-year perspective, finding global uncertainty both “terrifying” and “interesting,” offers hope that civilizational differences can enrich rather than threaten human development. His work suggests that Huntington’s dire predictions reflect a failure of imagination rather than inevitable destiny.

The choice between these paradigms is not merely intellectual but practical, shaping policies that either increase or decrease the likelihood of conflict. Wang’s framework offers a path toward what he calls “living with civilizations”—not in opposition or dominance, but in the creative tension that has characterized humanity’s greatest achievements.

In an era of rising civilizational consciousness, Wang Gungwu’s sophisticated alternative to Huntington’s clash paradigm offers essential wisdom for navigating diversity without surrendering to conflict. His work demonstrates that civilizations need not clash if we develop the institutional wisdom and cultural humility to let them coexist and enrich each other.

Competing Visions of Tomorrow: Long-term Extrapolations from Wang Gungwu and Huntington’s Frameworks

Introduction: Two Pathways Through the 21st Century

The intellectual frameworks of Wang Gungwu and Samuel Huntington offer fundamentally different trajectories for world history over the next 25-75 years. As we stand in 2025, with emerging evidence of a multipolar world order and a rising global civilizational consciousness, these competing visions offer contrasting roadmaps for humanity’s future. Wang’s synthesis-based civilizational pluralism suggests a path toward managed diversity and institutional innovation, while Huntington’s clash paradigm implies escalating conflict and potential civilizational dominance battles.

The Next Decade (2025-2035): Diverging Trajectories Begin

The Huntingtonian Path: Accelerating Civilizational Polarization

Under Huntington’s framework, current trends point toward increasing civilizational consolidation and conflict:

Phase 1: Civilizational Bloc Formation (2025-2030)

- The US-China trade war evolves into broader civilizational competition, with nations forced to choose sides

- Europe faces internal division between Christian and Islamic populations, potentially leading to political fragmentation

- Russia attempts to position itself as leader of a Orthodox-Slavic civilizational bloc

- India emerges as the dominant voice of Hindu civilization, potentially conflicting with Islamic neighbors

Phase 2: Institutional Breakdown (2030-2035) Current analysis suggests we’re moving toward “a more multipolar world without robust multilateral institutions.” Under Huntington’s logic, this would accelerate as civilizational differences make international cooperation increasingly difficult. The UN system would weaken further, replaced by civilizational alliance structures.

Conflict Intensification: Reports indicate that “multipolar competition increases the risk of military confrontations, trade wars, and regional instability, especially in conflict-prone areas such as Eastern Europe, the South China Sea, and the Middle East.” Huntington’s framework would predict that these regional conflicts would escalate into broader civilizational confrontations.

The Wang Gungwu Path: Institutional Innovation and Synthesis

Wang’s framework suggests a different trajectory based on constitutional pluralism and civilizational coexistence:

Phase 1: Multipolar Stabilization (2025-2030)

- China’s preference for multipolarity creates space for multiple civilizational approaches to modernity.

- Southeast Asian models of civilizational synthesis spread to other regions

- New institutional frameworks emerge that accommodate civilizational diversity without requiring uniformity

- Trade and technology cooperation continue despite political competition

Phase 2: Constitutional Innovation (2030-2035) Building on Singapore’s success, new forms of governance emerge that can manage civilizational plurality within coherent political systems. Regional organisations develop sophisticated mechanisms for civilizational coexistence.

The Mid-Century Transformation (2035-2050): Critical Juncture

Environmental and Demographic Pressures

Both frameworks must contend with mounting environmental challenges. Current projections suggest the human population will reach 9.75 billion by 2050, while climate change creates unprecedented stress on political systems. Some analyses warn that “human systems could reach a ‘point of no return'” by 2050, potentially leading to “the breakdown of nations and the international order.”

Huntington’s Environmental Dystopia: Under the clash paradigm, environmental stress accelerates civilizational conflict:

- Resource scarcity triggers “water wars” and “climate conflicts” along civilizational lines

- Mass migration creates civilizational friction as populations move across cultural boundaries

- Failed states become battlegrounds for civilizational influence

- Nuclear-armed civilizational blocs emerge as ultimate guarantors of survival

Wang’s Adaptive Synthesis: Wang’s framework suggests environmental challenges could catalyze civilizational cooperation:

- Crisis forces development of new institutional forms that transcend traditional boundaries

- Civilizational knowledge systems combine to address complex challenges (Chinese holistic thinking, Western scientific method, Islamic environmental ethics, Indian cyclical time concepts)

- Technology enables new forms of governance that accommodate diversity while enabling coordination

- Environmental cooperation becomes foundation for broader civilizational synthesis

Technological Transformation

Current trends indicate that “technological and military surprise were ‘black swans’ in 2025-2030,” with AI governance becoming a critical international challenge. The development of these technologies depends heavily on whether civilizational cooperation or competition prevails.

Huntington’s Tech Warfare:

- AI becomes a tool of civilizational competition, with different AI systems reflecting different cultural values

- Technological innovation concentrates within civilizational blocs, reducing global knowledge sharing

- Cyber warfare escalates along civilizational lines

- Technology reinforces rather than transcends cultural boundaries

Wang’s Civilizational Innovation:

- AI development benefits from multiple civilizational perspectives on intelligence, ethics, and human nature

- Technology enables new forms of cultural preservation and exchange

- Digital platforms facilitate civilizational dialogue and mutual learning

- Innovation emerges from civilizational synthesis rather than competition

The Late 21st Century (2050-2100): Institutional Crystallisation

Scenario A: The Huntingtonian End-State

By 2075-2100, Huntington’s logic leads to a world of consolidated civilizational blocs:

Civilizational Superstates:

- A Western bloc led by the US and Europe, emphasising individual rights and market capitalism

- A Sinic sphere dominated by China, extending through East Asia and parts of Africa

- An Islamic confederation stretching from North Africa through Central Asia

- An Indic region centred on India with Hindu-Buddhist characteristics

- Orthodox and other smaller civilizational entities in peripheral positions

Permanent Competition: These blocs exist in perpetual tension, with:

- Limited inter-civilizational trade and cultural exchange

- Competing international law systems based on different civilizational values

- Proxy conflicts in contested regions

- Arms races and territorial disputes as primary international relations

Internal Homogenization: Within each bloc, pressure for civilizational purity leads to:

- Suppression of minority cultures and alternative interpretations

- Educational systems emphasising civilizational superiority

- Limited individual mobility between civilizational zones

- Authoritarian governance justified by civilizational necessity

Scenario B: The Wang Gungwu Alternative

Wang’s framework envisions a different crystallization based on institutionalized plurality:

Civilizational Federalism: By 2075-2100, new forms of governance emerge that can accommodate multiple civilizational influences:

Global Institutional Innovation:

- International organisations restructured to represent civilizational diversity while maintaining functional effectiveness

- New forms of international law that accommodate different value systems while establishing common standards

- Economic systems that enable both civilizational autonomy and global integration

- Educational frameworks that teach multiple civilizational perspectives as complementary rather than competing

Regional Synthesis Models:

- Southeast Asian success in civilizational management spreads globally

- Africa develops unique syntheses of indigenous, Islamic, Christian, and modern influences

- Latin America integrates indigenous, European, and other civilizational elements

- Even Europe learns to manage Christian, secular, and Islamic influences constitutionally

Flexible Identity Systems:

- Individuals can maintain multiple civilizational affiliations without conflict

- Cities become laboratories for civilizational synthesis

- Technology enables the preservation of local cultures within global frameworks

- Migration and intermarriage create new forms of civilizational creativity

Critical Variables Determining Which Path Prevails

The Singapore Test

Wang repeatedly emphasizes Singapore as proof that civilizational synthesis is possible. Whether the “Singapore model” can scale globally will largely determine which framework proves prophetic. Current evidence suggests mixed results—some societies are successfully managing diversity while others are fragmenting along cultural lines.

Chinese Strategic Choices

Wang’s insight that China prefers multipolarity to bipolarity becomes crucial. If China continues to pursue “room to maneuver” rather than civilizational dominance, it supports Wang’s framework. If domestic pressures or external threats prompt China to assume civilizational leadership, it would validate Huntington’s predictions.

American Adaptation

Wang’s observation that “the US is starting to become more like China” suggests that America is adapting to a multipolar reality. Whether the US can develop new approaches to global leadership that accommodate civilizational diversity will have a significant impact on global trajectories.

Institutional Innovation

The key variable may be humanity’s capacity for constitutional innovation. Wang’s framework requires the development of new institutional forms that current political science barely imagines. Huntington’s path represents the failure of such innovation, reverting to familiar patterns of competitive state behaviour.

Wild Cards and Black Swan Events

Positive Disruptions

- Breakthrough technologies that make resource scarcity obsolete

- Contact with extraterrestrial intelligence that forces civilizational cooperation

- Environmental crises so severe they override civilizational differences

- Religious or philosophical movements that transcend civilizational boundaries

Negative Disruptions

- Nuclear conflict that destroys existing civilizational centers

- Pandemic diseases that fragment global systems

- Climate collapse that makes civilizational development impossible

- AI development that transcends human civilizational categories entirely

Implications for Current Decision-Making

For Policymakers

If Wang is Right:

- Invest in institutional innovation that accommodates diversity

- Develop constitutional frameworks for managing civilizational plurality

- Foster inter-civilizational dialogue and exchange

- Create educational systems that teach civilizational appreciation

If Huntington is Right:

- Strengthen civilizational alliances and bloc formation

- Prepare for long-term civilizational competition

- Develop strategies for civilizational coherence and loyalty

- Build defensive capabilities against civilizational rivals

For Individuals

Wang’s Path Requires:

- Cultural humility and willingness to learn from different civilizations

- Development of multiple civilizational competencies

- Support for institutional experimentation and constitutional innovation

- Patience with the messiness of civilizational synthesis

Huntington’s Path Implies:

- Strong identification with particular civilizational traditions

- Preparation for civilizational competition and potential conflict

- Loyalty to civilizational institutions and values

- Skepticism toward synthesis and cosmopolitan approaches

The Meta-Question: Prediction vs. Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Perhaps the most important insight is that both frameworks contain elements of self-fulfilling prophecy. If enough people believe civilizations must clash, they create conditions that make clash more likely. If enough people work toward civilizational synthesis, they create possibilities for coexistence.

Wang’s 94-year perspective offers wisdom here: his ability to find uncertainty both “terrifying” and “interesting” suggests that the future remains open to human agency and institutional creativity. Huntington’s framework, while analytically powerful, may represent a failure of imagination about human adaptability.

Conclusion: Choosing Our Civilizational Future

The extrapolation of Wang Gungwu and Huntington’s frameworks reveals that we stand at a critical juncture in human history. The next 25 years will largely determine whether humanity develops the institutional wisdom to manage civilizational diversity or falls back into patterns of competitive conflict that could define the remainder of the 21st century.

Current trends suggest elements of both pathways are emerging simultaneously. The challenge for human civilization is to consciously choose which trajectory to emphasize through policy, institution-building, and individual behavior.

Wang’s framework offers hope that civilizational differences can enrich rather than threaten human development, but it requires unprecedented levels of institutional innovation and cultural humility. Huntington’s framework represents the path of least resistance—familiar patterns of competitive behavior that require no new thinking but may ultimately prove catastrophic in an interconnected world facing global challenges.

The choice between these futures may be one of the most critical decisions humanity makes in the coming decades. As Wang suggests, the uncertainties are indeed terrifying, but they are also what make life—and history—interesting. The future remains unwritten, awaiting the institutional creativity and cultural wisdom that will determine whether human civilisations clash or coexist in the centuries ahead.

Maxthon

In an age where the digital world is in constant flux and our interactions online are ever-evolving, the importance of prioritising individuals as they navigate the expansive internet cannot be overstated. The myriad of elements that shape our online experiences calls for a thoughtful approach to selecting web browsers—one that places a premium on security and user privacy. Amidst the multitude of browsers vying for users’ loyalty, Maxthon emerges as a standout choice, providing a trustworthy solution to these pressing concerns, all without any cost to the user.

Maxthon, with its advanced features, boasts a comprehensive suite of built-in tools designed to enhance your online privacy. Among these tools are a highly effective ad blocker and a range of anti-tracking mechanisms, each meticulously crafted to fortify your digital sanctuary. This browser has carved out a niche for itself, particularly with its seamless compatibility with Windows 11, further solidifying its reputation in an increasingly competitive market.

In a crowded landscape of web browsers, Maxthon has forged a distinct identity through its unwavering dedication to offering a secure and private browsing experience. Fully aware of the myriad threats lurking in the vast expanse of cyberspace, Maxthon works tirelessly to safeguard your personal information. Utilizing state-of-the-art encryption technology, it ensures that your sensitive data remains protected and confidential throughout your online adventures.

What truly sets Maxthon apart is its commitment to enhancing user privacy during every moment spent online. Each feature of this browser has been meticulously designed with the user’s privacy in mind. Its powerful ad-blocking capabilities work diligently to eliminate unwanted advertisements, while its comprehensive anti-tracking measures effectively reduce the presence of invasive scripts that could disrupt your browsing enjoyment. As a result, users can traverse the web with newfound confidence and safety.

Moreover, Maxthon’s incognito mode provides an extra layer of security, granting users enhanced anonymity while engaging in their online pursuits. This specialised mode not only conceals your browsing habits but also ensures that your digital footprint remains minimal, allowing for an unobtrusive and liberating internet experience. With Maxthon as your ally in the digital realm, you can explore the vastness of the internet with peace of mind, knowing that your privacy is being prioritised every step of the way.