Recent data reveals a troubling decline in the credit health of American consumers. In April 2025, the average FICO score fell to 715, down from 717 the previous year, representing the sharpest annual drop since the financial crisis of 2008-2009.

One major factor contributing to this decline is rising credit utilization. According to FICO, Americans used 35.5% of their available credit in April 2025, compared to just 29.6% in April 2021. This increase signals that many households are relying more heavily on credit amid persistent inflation and elevated interest rates.

Additionally, student loan delinquencies have surged following the expiration of COVID-era protections. With the end of payment pauses and temporary credit reporting relief in September 2024, missed student loan payments started appearing on credit reports as early as February 2025. FICO reports that 3.1% of scored consumers had new student loan delinquencies added to their files between February and April 2025.

The impact of these trends is not distributed equally across age groups. Data show that Generation Z borrowers have experienced the most significant drops in credit scores, indicating heightened financial vulnerability among younger adults.

In summary, higher credit usage and a resurgence in student loan delinquencies are driving a notable deterioration in American credit health. If these trends persist, they could signal broader risks for household finances and economic stability.

Credit Crisis Lessons: What Singapore Can Learn from America’s Score Decline

The steepest drop in US credit scores since the 2008 financial crisis offers critical insights for Singapore’s banking sector, financial markets, and consumers navigating an uncertain economic landscape.

The American Warning Signal

The numbers from across the Pacific are stark: American credit scores have fallen at their fastest pace since the Great Recession, with the average FICO score dropping to 715 in April 2025 from 717 the previous year. While a two-point decline might seem modest, it represents the most significant deterioration in consumer creditworthiness in over 15 years—a canary in the coal mine that Singapore’s financial ecosystem cannot afford to ignore.

The parallels between the US situation and Singapore’s current economic environment are more pronounced than they initially appear. Both economies are grappling with persistent inflation, elevated interest rates, and households stretching to maintain their standard of living. However, Singapore’s unique financial landscape—characterized by different debt structures, regulatory frameworks, and consumer behaviors—presents both opportunities to avoid similar pitfalls and distinct vulnerabilities that require proactive management.

Dissecting the American Decline

The US credit score deterioration stems from two primary factors that offer instructive lessons for Singapore. First, credit utilization ratios have surged from 29.6% in April 2021 to 35.5% in April 2025, reflecting households increasingly relying on credit cards and revolving credit to bridge gaps between income and expenses. This pattern suggests that the post-pandemic economic recovery has been uneven, with many consumers still struggling to rebuild financial buffers depleted during the crisis.

Second, the return of student loan obligations has created a delayed reckoning. After years of payment pauses and deferred reporting, student loan delinquencies began appearing on credit reports in February 2025, affecting 3.1% of scored consumers within just three months. This delayed impact demonstrates how government intervention programs, while providing crucial short-term relief, can create concentrated risks when they expire.

The generational impact has been particularly severe, with Gen Z experiencing the largest credit score declines. This cohort faces a perfect storm: higher education debt burdens, limited time to build savings, reduced benefit from asset appreciation, and greater exposure to inflation’s impact on discretionary spending.

Singapore’s Distinct Financial Landscape

Singapore’s financial system operates under fundamentally different principles that both insulate it from and expose it to similar risks. The city-state’s mandatory Central Provident Fund (CPF) system provides a forced savings mechanism that Americans lack, creating a financial foundation that can weather economic storms more effectively. However, this same system creates unique vulnerabilities, particularly around housing finance and retirement adequacy.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has already demonstrated awareness of credit risks through multiple cooling measures in the property market and progressive tightening of lending standards. The Total Debt Servicing Ratio (TDSR) framework, which caps household debt servicing at 60% of gross monthly income, provides a structural safeguard against over-leveraging that the US system lacks.

Yet Singapore faces its own version of the American credit utilization problem. Household debt-to-GDP ratios have risen steadily, reaching levels that, while manageable in the current interest rate environment, could become problematic if economic conditions deteriorate. The prevalence of variable-rate mortgages means Singaporean households are more immediately exposed to interest rate changes than their American counterparts, who predominantly hold fixed-rate mortgages.

Banking Sector Implications: Proactive Risk Management

Singapore’s banking sector should extract three critical lessons from the American experience. First, the importance of forward-looking risk assessment cannot be overstated. The US credit score decline reflects economic stresses that have been building for years but only recently materialized in credit metrics. Singapore banks should enhance their early warning systems, focusing on leading indicators of financial stress rather than lagging measures like delinquency rates.

The student loan crisis in America highlights how government support programs can create concentrated risks when they expire. Singapore’s various support schemes—from rental relief to loan moratoriums—require careful monitoring as they wind down. Banks should prepare for potential increases in delinquencies as borrowers who have been shielded from payment obligations face the full reality of their debt burdens.

Second, generational risk profiling needs sophisticated refinement. The disproportionate impact on Gen Z in America suggests that traditional credit scoring models may not adequately capture the financial vulnerabilities of younger borrowers. Singapore banks should develop nuanced approaches to assessing creditworthiness across different age cohorts, considering factors like career trajectory, asset accumulation potential, and exposure to macroeconomic shocks.

Third, the credit utilization surge in America demonstrates how consumers use revolving credit as a financial shock absorber. Singapore banks should monitor credit card utilization patterns closely, as increases could signal broader household financial stress. The relatively higher usage of debit cards and electronic payments in Singapore might mask some of this stress, making it crucial to look beyond traditional credit metrics.

Market-Level Systemic Risks

From a systemic perspective, the American credit deterioration reveals how seemingly disparate economic factors can converge to create broad-based financial stress. Singapore’s financial markets should prepare for similar convergence risks, particularly around the intersection of housing finance, employment stability, and interest rate sensitivity.

The property market represents Singapore’s most significant systemic risk parallel to America’s student loan situation. While Singapore’s property cooling measures have prevented the kind of speculative excess seen in other markets, the combination of high property prices, substantial household leverage to real estate, and interest rate sensitivity creates a concentrated risk point. Unlike America’s student loans, which affect primarily younger demographics, Singapore’s property exposure cuts across all age groups and income levels.

Currency dynamics add another layer of complexity absent from the American domestic situation. Singapore’s small, open economy means that global financial conditions directly impact domestic credit conditions through exchange rate and capital flow channels. Banks and regulators must consider how external shocks could amplify domestic credit stress, particularly for borrowers with foreign currency exposure or those employed in trade-dependent sectors.

Consumer-Level Lessons: Financial Resilience Building

Singapore consumers can learn valuable lessons from the American experience about building financial resilience in an uncertain environment. The surge in credit utilization rates in America demonstrates how quickly household finances can deteriorate when faced with persistent inflation and stagnant real wages.

The first lesson is the critical importance of maintaining low credit utilization ratios during good times. American consumers who entered the current period with high credit utilization had little room to maneuver when economic conditions tightened. Singapore consumers should aim to keep credit utilization well below available limits, treating credit cards as payment convenience tools rather than financing mechanisms.

Second, the delayed impact of the student loan crisis shows how deferred financial obligations can create false security. Singapore consumers should be wary of assuming that current low-interest-rate environments or government support programs will persist indefinitely. Building financial buffers during favorable conditions becomes crucial for weathering inevitable economic cycles.

The generational impact in America also offers insights for Singapore’s younger consumers. Gen Z Americans suffered disproportionately because they had limited time to build financial resilience before facing economic headwinds. Singapore’s younger consumers should prioritize emergency fund building and debt reduction, even if it means constraining current consumption.

Policy Implications: Balancing Support and Sustainability

The American experience offers sobering lessons about the long-term consequences of well-intentioned support programs. The student loan payment pause provided crucial relief during the pandemic but created a concentrated risk when protections expired. Singapore policymakers should consider how current support measures might create similar delayed impacts.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore’s macroprudential tools provide more sophisticated options for managing systemic risks than those available to American regulators. However, the effectiveness of these tools depends on timely deployment and appropriate calibration. The American credit score decline suggests that by the time traditional indicators show stress, underlying vulnerabilities may already be deeply entrenched.

Singapore’s unique position as both a financial center and a domestic economy creates additional policy complexity. Measures designed to maintain the city-state’s competitiveness as a financial hub might conflict with domestic financial stability objectives. The American experience suggests that prioritizing long-term financial stability over short-term growth considerations ultimately serves both objectives better.

Technology and Innovation Opportunities

The American credit crisis also highlights opportunities for technological innovation in credit assessment and risk management. Traditional credit scoring models, designed for stable economic environments, may not adequately capture risks in today’s volatile conditions. Singapore’s advanced digital infrastructure and regulatory openness to fintech innovation position it well to develop more sophisticated credit assessment tools.

Alternative data sources—from digital payment patterns to social media activity—could provide earlier warning signs of financial stress than traditional credit bureau data. Singapore’s Smart Nation initiative and comprehensive digital payment ecosystem generate vast amounts of potentially useful financial behavior data.

Machine learning and artificial intelligence applications could help identify subtle patterns in consumer behavior that predict credit deterioration before it appears in traditional metrics. However, the American experience also demonstrates the importance of maintaining human oversight and avoiding the kind of algorithmic bias that could exacerbate existing inequalities.

Building a More Resilient Financial Ecosystem

The American credit score decline ultimately reflects systemic weaknesses in financial resilience at multiple levels—individual, institutional, and regulatory. Singapore’s different starting point provides opportunities to build a more robust system, but only with proactive effort and clear-eyed assessment of vulnerabilities.

For banks, this means investing in sophisticated risk management capabilities, maintaining conservative lending standards even during good times, and developing deep understanding of customer financial behavior across different economic cycles. The temptation to ease credit standards during competitive pressure must be resisted in favor of long-term stability.

For consumers, the lessons center on building genuine financial resilience rather than relying on available credit as a safety net. This means maintaining emergency funds, keeping debt levels manageable relative to income, and planning for economic volatility rather than assuming current conditions will persist.

For policymakers, the American experience demonstrates both the value and limitations of intervention programs. While support measures can provide crucial relief during crises, their design must carefully consider long-term consequences and exit strategies. Singapore’s strong institutional capacity provides advantages in implementing and unwinding such programs effectively.

The Path Forward

The American credit score decline serves as a valuable early warning system for Singapore’s financial ecosystem. While the specific circumstances differ, the underlying dynamics—household financial stress, delayed policy consequences, and generational vulnerabilities—offer universal lessons.

Singapore’s challenge is to learn these lessons proactively rather than reactively. The city-state’s strong regulatory framework, sophisticated financial institutions, and fiscally prudent population provide a solid foundation for weathering economic storms. However, these advantages must not breed complacency.

The American experience suggests that financial vulnerabilities can build gradually before manifesting suddenly. Singapore’s financial ecosystem must remain vigilant, maintaining robust risk management practices, conservative lending standards, and strong household financial resilience even during periods of apparent stability.

Ultimately, the goal is not merely to avoid America’s current difficulties but to build a financial system that can adapt and thrive regardless of economic conditions. The American credit crisis offers a roadmap of pitfalls to avoid and a reminder that financial stability requires constant vigilance and proactive management.

The two-point decline in American credit scores may seem small, but it represents the accumulated weight of millions of individual financial decisions and systemic policy choices. Singapore has the opportunity to learn from this experience and build a more resilient financial future—but only if it acts on these lessons before facing its own moment of reckoning.

Credit Crisis Lessons: What Singapore Can Learn from America’s Score Decline

The steepest drop in US credit scores since the 2008 financial crisis offers critical insights for Singapore’s banking sector, financial markets, and consumers navigating an uncertain economic landscape.

The American Warning Signal

The numbers from across the Pacific are stark: American credit scores have fallen at their fastest pace since the Great Recession, with the average FICO score dropping to 715 in April 2025 from 717 the previous year. While a two-point decline might seem modest, it represents the most significant deterioration in consumer creditworthiness in over 15 years—a canary in the coal mine that Singapore’s financial ecosystem cannot afford to ignore.

The parallels between the US situation and Singapore’s current economic environment are more pronounced than they initially appear. Both economies are grappling with persistent inflation, elevated interest rates, and households stretching to maintain their standard of living. However, Singapore’s unique financial landscape—characterized by different debt structures, regulatory frameworks, and consumer behaviors—presents both opportunities to avoid similar pitfalls and distinct vulnerabilities that require proactive management.

Dissecting the American Decline

The US credit score deterioration stems from two primary factors that offer instructive lessons for Singapore. First, credit utilization ratios have surged from 29.6% in April 2021 to 35.5% in April 2025, reflecting households increasingly relying on credit cards and revolving credit to bridge gaps between income and expenses. This pattern suggests that the post-pandemic economic recovery has been uneven, with many consumers still struggling to rebuild financial buffers depleted during the crisis.

Second, the return of student loan obligations has created a delayed reckoning. After years of payment pauses and deferred reporting, student loan delinquencies began appearing on credit reports in February 2025, affecting 3.1% of scored consumers within just three months. This delayed impact demonstrates how government intervention programs, while providing crucial short-term relief, can create concentrated risks when they expire.

The generational impact has been particularly severe, with Gen Z experiencing the largest credit score declines. This cohort faces a perfect storm: higher education debt burdens, limited time to build savings, reduced benefit from asset appreciation, and greater exposure to inflation’s impact on discretionary spending.

Singapore’s Distinct Financial Landscape

Singapore’s financial system operates under fundamentally different principles that both insulate it from and expose it to similar risks. The city-state’s mandatory Central Provident Fund (CPF) system provides a forced savings mechanism that Americans lack, creating a financial foundation that can weather economic storms more effectively. However, this same system creates unique vulnerabilities, particularly around housing finance and retirement adequacy.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has already demonstrated awareness of credit risks through multiple cooling measures in the property market and progressive tightening of lending standards. The Total Debt Servicing Ratio (TDSR) framework, which caps household debt servicing at 60% of gross monthly income, provides a structural safeguard against over-leveraging that the US system lacks.

Yet Singapore faces its own version of the American credit utilization problem. Household debt-to-GDP ratios have risen steadily, reaching levels that, while manageable in the current interest rate environment, could become problematic if economic conditions deteriorate. The prevalence of variable-rate mortgages means Singaporean households are more immediately exposed to interest rate changes than their American counterparts, who predominantly hold fixed-rate mortgages.

Banking Sector Implications: Proactive Risk Management

Singapore’s banking sector should extract three critical lessons from the American experience. First, the importance of forward-looking risk assessment cannot be overstated. The US credit score decline reflects economic stresses that have been building for years but only recently materialized in credit metrics. Singapore banks should enhance their early warning systems, focusing on leading indicators of financial stress rather than lagging measures like delinquency rates.

The student loan crisis in America highlights how government support programs can create concentrated risks when they expire. Singapore’s various support schemes—from rental relief to loan moratoriums—require careful monitoring as they wind down. Banks should prepare for potential increases in delinquencies as borrowers who have been shielded from payment obligations face the full reality of their debt burdens.

Second, generational risk profiling needs sophisticated refinement. The disproportionate impact on Gen Z in America suggests that traditional credit scoring models may not adequately capture the financial vulnerabilities of younger borrowers. Singapore banks should develop nuanced approaches to assessing creditworthiness across different age cohorts, considering factors like career trajectory, asset accumulation potential, and exposure to macroeconomic shocks.

Third, the credit utilization surge in America demonstrates how consumers use revolving credit as a financial shock absorber. Singapore banks should monitor credit card utilization patterns closely, as increases could signal broader household financial stress. The relatively higher usage of debit cards and electronic payments in Singapore might mask some of this stress, making it crucial to look beyond traditional credit metrics.

Market-Level Systemic Risks

From a systemic perspective, the American credit deterioration reveals how seemingly disparate economic factors can converge to create broad-based financial stress. Singapore’s financial markets should prepare for similar convergence risks, particularly around the intersection of housing finance, employment stability, and interest rate sensitivity.

The property market represents Singapore’s most significant systemic risk parallel to America’s student loan situation. While Singapore’s property cooling measures have prevented the kind of speculative excess seen in other markets, the combination of high property prices, substantial household leverage to real estate, and interest rate sensitivity creates a concentrated risk point. Unlike America’s student loans, which affect primarily younger demographics, Singapore’s property exposure cuts across all age groups and income levels.

Currency dynamics add another layer of complexity absent from the American domestic situation. Singapore’s small, open economy means that global financial conditions directly impact domestic credit conditions through exchange rate and capital flow channels. Banks and regulators must consider how external shocks could amplify domestic credit stress, particularly for borrowers with foreign currency exposure or those employed in trade-dependent sectors.

Consumer-Level Lessons: Financial Resilience Building

Singapore consumers can learn valuable lessons from the American experience about building financial resilience in an uncertain environment. The surge in credit utilization rates in America demonstrates how quickly household finances can deteriorate when faced with persistent inflation and stagnant real wages.

The first lesson is the critical importance of maintaining low credit utilization ratios during good times. American consumers who entered the current period with high credit utilization had little room to maneuver when economic conditions tightened. Singapore consumers should aim to keep credit utilization well below available limits, treating credit cards as payment convenience tools rather than financing mechanisms.

Second, the delayed impact of the student loan crisis shows how deferred financial obligations can create false security. Singapore consumers should be wary of assuming that current low-interest-rate environments or government support programs will persist indefinitely. Building financial buffers during favorable conditions becomes crucial for weathering inevitable economic cycles.

The generational impact in America also offers insights for Singapore’s younger consumers. Gen Z Americans suffered disproportionately because they had limited time to build financial resilience before facing economic headwinds. Singapore’s younger consumers should prioritize emergency fund building and debt reduction, even if it means constraining current consumption.

Policy Implications: Balancing Support and Sustainability

The American experience offers sobering lessons about the long-term consequences of well-intentioned support programs. The student loan payment pause provided crucial relief during the pandemic but created a concentrated risk when protections expired. Singapore policymakers should consider how current support measures might create similar delayed impacts.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore’s macroprudential tools provide more sophisticated options for managing systemic risks than those available to American regulators. However, the effectiveness of these tools depends on timely deployment and appropriate calibration. The American credit score decline suggests that by the time traditional indicators show stress, underlying vulnerabilities may already be deeply entrenched.

Singapore’s unique position as both a financial center and a domestic economy creates additional policy complexity. Measures designed to maintain the city-state’s competitiveness as a financial hub might conflict with domestic financial stability objectives. The American experience suggests that prioritizing long-term financial stability over short-term growth considerations ultimately serves both objectives better.

Technology and Innovation Opportunities

The American credit crisis also highlights opportunities for technological innovation in credit assessment and risk management. Traditional credit scoring models, designed for stable economic environments, may not adequately capture risks in today’s volatile conditions. Singapore’s advanced digital infrastructure and regulatory openness to fintech innovation position it well to develop more sophisticated credit assessment tools.

Alternative data sources—from digital payment patterns to social media activity—could provide earlier warning signs of financial stress than traditional credit bureau data. Singapore’s Smart Nation initiative and comprehensive digital payment ecosystem generate vast amounts of potentially useful financial behavior data.

Machine learning and artificial intelligence applications could help identify subtle patterns in consumer behavior that predict credit deterioration before it appears in traditional metrics. However, the American experience also demonstrates the importance of maintaining human oversight and avoiding the kind of algorithmic bias that could exacerbate existing inequalities.

Bank-by-Bank Scenario Analysis: Institutional Vulnerabilities and Strengths

The American credit crisis offers an opportunity to examine how Singapore’s major banking institutions might fare under similar stress conditions. Each bank’s unique business model, customer base, and risk management approach creates different vulnerability profiles that warrant individual analysis.

DBS Bank: The Universal Banking Challenge

As Singapore’s largest bank and a regional powerhouse, DBS faces the most complex risk profile in a credit deterioration scenario. The bank’s strength lies in its diversified revenue streams and sophisticated risk management infrastructure, developed through multiple economic cycles. However, its size and market dominance also create unique vulnerabilities.

DBS’s extensive mortgage portfolio represents both a competitive advantage and a concentration risk. While Singapore’s property cooling measures have maintained relative stability, a scenario mirroring the American credit decline could see property-related stress emerge through multiple channels. Unlike American banks that primarily hold fixed-rate mortgages, DBS’s variable-rate mortgage book would immediately reflect interest rate increases in customer payment burdens.

The bank’s regional expansion strategy adds another layer of complexity absent from pure domestic players. Credit deterioration in key markets like Hong Kong, Taiwan, or mainland China could compound domestic Singaporean stress. DBS’s strong capital position provides buffers, but the interconnected nature of regional economies means that a credit crisis rarely remains contained to single markets.

In a stress scenario, DBS would likely benefit from its technological investments and data analytics capabilities, enabling more granular risk assessment and early intervention. However, the bank’s large retail customer base means it would face the full brunt of any consumer credit deterioration, particularly among younger demographics who form a significant portion of its digital banking customers.

OCBC Bank: Conservative Positioning with Hidden Risks

OCBC’s traditionally conservative approach to lending and risk management positions it well for weathering credit storms. The bank’s emphasis on relationship banking and higher-net-worth customers provides some insulation from the kind of broad-based consumer stress seen in America. However, this positioning creates its own vulnerabilities.

The bank’s significant exposure to private banking and wealth management means it’s particularly sensitive to market volatility and asset price corrections. While American-style credit score declines might not directly impact OCBC’s wealth management clients, the underlying economic conditions that cause such declines—inflation, interest rate stress, economic uncertainty—directly affect investment portfolios and client risk appetite.

OCBC’s commercial banking portfolio presents both opportunities and risks in a stress scenario. The bank’s focus on established businesses and conservative lending practices should limit outright defaults. However, economic stress that leads to consumer credit deterioration often translates into reduced business revenues, particularly for companies serving domestic markets. OCBC’s commercial clients in retail, hospitality, and consumer services could face significant pressures.

The bank’s insurance operations through Great Eastern add another dimension of complexity. Life insurance and investment-linked products could face higher lapses and reduced new business in an economic downturn, while general insurance might see increased claims from stressed policyholders. This diversification provides some revenue stability but also creates cross-sector risk correlations.

In a credit stress scenario, OCBC’s conservative culture would likely serve it well, enabling quick recognition of problems and proactive risk management. However, the bank’s higher cost base and emphasis on relationship banking could pressure profitability if economic conditions deteriorate significantly.

UOB Bank: Regional Exposure and Sector Concentrations

UOB’s strong regional presence, particularly in Southeast Asia, creates a risk profile distinct from its domestic competitors. The bank’s exposure to Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia means that credit stress scenarios must consider broader regional economic conditions, not just domestic Singaporean factors.

The bank’s significant exposure to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) across the region represents both a competitive strength and a vulnerability. SMEs typically experience credit stress earlier and more acutely than larger corporations, making UOB potentially more sensitive to early-stage economic deterioration. However, the bank’s deep relationships with these businesses and understanding of local markets provide advantages in managing through difficulties.

UOB’s art and cultural investments, while enhancing brand value, also reflect a customer base with discretionary wealth that could quickly evaporate in economic stress. The bank’s focus on affluent individuals and family businesses means it would be particularly exposed to the kind of asset price corrections that often accompany broad-based credit deterioration.

The bank’s significant property development financing portfolio requires careful scenario analysis. Unlike residential mortgages, development financing faces both demand-side risks (reduced property purchases) and supply-side risks (construction cost inflation, labor shortages). A scenario combining American-style consumer stress with Singapore’s property market vulnerabilities could create compounded risks for UOB.

In managing through a credit crisis, UOB’s regional diversification could provide some offset to domestic Singaporean stress, but only if regional economies remain resilient. The bank’s strong capital position and conservative provisioning practices provide buffers, but its SME focus means credit losses could emerge quickly once economic conditions deteriorate.

Scenario Modeling: Three Stress Cases

Moderate Stress Scenario: Credit utilization rises to American levels (35%+), with corresponding increases in delinquencies but no major economic shock. In this scenario, DBS faces the broadest exposure across all customer segments but benefits from diversification. OCBC’s conservative positioning limits direct losses but faces margin pressure from increased funding costs. UOB experiences early stress in its SME portfolio but regional diversification provides some offset.

Severe Stress Scenario: Credit deterioration combines with property market correction and regional economic slowdown. DBS faces significant mortgage portfolio stress and regional contagion effects. OCBC’s wealth management business suffers from market volatility and reduced client activity. UOB experiences compounded stress from both domestic property exposure and regional SME difficulties.

Systemic Crisis Scenario: Credit stress combines with external shocks (global recession, major trading partner difficulties, currency crisis). All three banks face significant challenges, but institutional strengths become critical. DBS’s technological capabilities and government relationships provide advantages. OCBC’s conservative balance sheet and capital strength enable survival. UOB’s regional presence becomes a liability requiring careful management.

Comparative Institutional Preparedness

Each bank’s risk management evolution since the 2008 financial crisis provides insights into crisis preparedness. DBS has invested heavily in technology and analytics, creating capabilities for sophisticated risk assessment and early intervention. This technological advantage could prove crucial in managing through consumer credit deterioration, enabling more granular customer management and proactive risk mitigation.

OCBC’s emphasis on relationship banking and conservative credit culture provides qualitative advantages that may not show up in quantitative risk models. The bank’s deeper customer relationships could enable better workout arrangements and reduced ultimate losses, even if early warning indicators suggest higher risk.

UOB’s regional experience and local market knowledge create advantages in managing through diverse economic conditions. The bank’s exposure to multiple economies and regulatory environments has built institutional resilience and crisis management capabilities that could prove valuable in navigating complex stress scenarios.

Strategic Implications for Each Institution

The American credit crisis suggests that banks with diversified business models and conservative risk cultures fare better in stress scenarios. However, each Singapore bank’s unique positioning requires different strategic approaches to building resilience.

DBS should leverage its technological capabilities to enhance early warning systems and customer intervention programs. The bank’s size and market position enable investments in sophisticated risk management that smaller competitors cannot match. However, this scale also requires careful attention to concentration risks and systemic impacts.

OCBC’s conservative positioning provides a strong foundation, but the bank should consider whether its risk-averse culture might limit appropriate growth opportunities. The challenge is maintaining conservative standards while ensuring adequate returns and market relevance.

UOB’s regional focus requires sophisticated understanding of cross-border risk correlations and contagion effects. The bank should enhance its capabilities for managing through diverse economic conditions simultaneously, as regional economic cycles become increasingly interconnected.

All three institutions should learn from the American experience about the importance of proactive provisioning, conservative underwriting standards, and maintaining strong capital buffers even during apparently favorable economic conditions. The American credit score decline demonstrates how quickly conditions can deteriorate once underlying vulnerabilities reach critical thresholds.

The American credit score decline ultimately reflects systemic weaknesses in financial resilience at multiple levels—individual, institutional, and regulatory. Singapore’s different starting point provides opportunities to build a more robust system, but only with proactive effort and clear-eyed assessment of vulnerabilities.

For banks, this means investing in sophisticated risk management capabilities, maintaining conservative lending standards even during good times, and developing deep understanding of customer financial behavior across different economic cycles. The temptation to ease credit standards during competitive pressure must be resisted in favor of long-term stability.

For consumers, the lessons center on building genuine financial resilience rather than relying on available credit as a safety net. This means maintaining emergency funds, keeping debt levels manageable relative to income, and planning for economic volatility rather than assuming current conditions will persist.

For policymakers, the American experience demonstrates both the value and limitations of intervention programs. While support measures can provide crucial relief during crises, their design must carefully consider long-term consequences and exit strategies. Singapore’s strong institutional capacity provides advantages in implementing and unwinding such programs effectively.

The Path Forward

The American credit score decline serves as a valuable early warning system for Singapore’s financial ecosystem. While the specific circumstances differ, the underlying dynamics—household financial stress, delayed policy consequences, and generational vulnerabilities—offer universal lessons.

Singapore’s challenge is to learn these lessons proactively rather than reactively. The city-state’s strong regulatory framework, sophisticated financial institutions, and fiscally prudent population provide a solid foundation for weathering economic storms. However, these advantages must not breed complacency.

The American experience suggests that financial vulnerabilities can build gradually before manifesting suddenly. Singapore’s financial ecosystem must remain vigilant, maintaining robust risk management practices, conservative lending standards, and strong household financial resilience even during periods of apparent stability.

Ultimately, the goal is not merely to avoid America’s current difficulties but to build a financial system that can adapt and thrive regardless of economic conditions. The American credit crisis offers a roadmap of pitfalls to avoid and a reminder that financial stability requires constant vigilance and proactive management.

The two-point decline in American credit scores may seem small, but it represents the accumulated weight of millions of individual financial decisions and systemic policy choices. Singapore has the opportunity to learn from this experience and build a more resilient financial future—but only if it acts on these lessons before facing its own moment of reckoning.

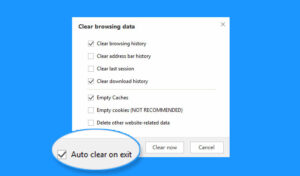

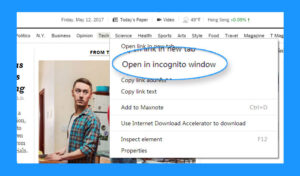

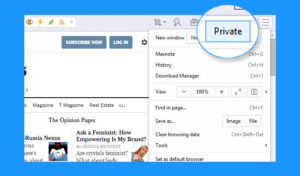

Instructions for Enabling and Disabling Private Browsing Mode in Maxthon Browser

1. Open Maxthon Browser: Launch the Maxthon browser on your device. Ensure you are running the latest version for optimal features and security.

2. Access the Menu: Click on the menu icon located at the top-right corner of the browser window. Three horizontal lines or dots usually represent this.

3. Select Private Browsing: In the dropdown menu, look for the Private Browsing option. Click on it to activate private mode.

4. Confirm Activation: A new window should appear, indicating that you are now in private browsing mode. You may notice a different colour scheme or an icon indicating this status.

5. Browse Privately: While in this mode, your browsing history, cookies, and site data will not be saved once you close the session. Feel free to explore securely.

6. Exit Private Browsing Mode: To return to regular browsing, click again on the menu icon and select Exit Private Browsing from the list of options.

7. Confirm Exit: Once you exit, a message may confirm that you have returned to normal browsing mode.

8. Resume Normal Usage: Continue surfing the internet without any restrictions while your activity is logged as usual again.

9. Check Settings if Needed: If you do not see these options, verify that your browser settings have not turned off private browsing functionality or consult the help section for troubleshooting advice.

Follow these steps carefully to navigate between standard and private modes seamlessly!