Financial institutions regularly use device identity for fraud prevention and to authenticate users at login or for high-risk activity. It is one of many controls that can be used to safeguard online interactions. But as with other security tools that rely on static measures, cybercriminals are finding ways to circumvent it. Taking over customer accounts is one fraud method causing the most financial impact on financial institutions – and the biggest headache. In a recent study, 72% of global banks cited account takeover as a leading cause of concern.

In addition, financial institutions are experiencing significant rates of fraud in the account opening process and have difficulty accurately distinguishing genuine applicants from cyber criminals. As financial institutions rely on growing their business through new customer acquisition, the creation of illegitimate accounts can have a huge business impact. Because new customers have never been seen before, their devices haven’t either, making device identity unhelpful for protecting against new account fraud.

The bottom line: Device identity is slowly eroding in value over time because it does not provide sufficient visibility beyond login and when opening digital accounts.

What Is Device Identity?

Digital identity is based on three aspects, which are also known as three factors of authentication that can be used to assert one’s digital identity: what you know, what you have, and who you are.

What You Know: Static information only the identity holder should know, such as personally identifiable information (PII) like phone numbers, past addresses, Social Security numbers, or passwords.

What You Have: A unique token or a device used to verify your identity by possession.

Who You Are: Biometrics such as fingerprints, faces, voices, or specific user behaviour are based on how an individual interacts with a device, like tap pressure and swipe patterns or how they enter information into a form.

Device identity falls into the “what you have” category, and it’s a unique identifier of the device, such as a cookie or other mechanism. An advanced form of device ID is device fingerprinting, which collects unique information about a device that can then be used to link the device to an individual user. The tool will collect data on browser, operating system, internet connection, IP address, geo-location, and more.

Device identity is categorised under the what you have classification, serving as a distinctive marker for a device akin to a cookie or an alternative identification method. A more sophisticated variant of this concept is device fingerprinting, which gathers specific data about a device that can be utilised to associate it with an individual user. This process involves collecting various types of information, such as details about the browser being used, the operating system in place, internet connectivity specifics, IP address information, geographic location data, and additional parameters.

However, relying solely on device ID leads to significant vulnerabilities in digital identity verification. The initial two categories—device ID and knowledge-based identifiers—are no longer adequate for confirming one’s digital identity due to the increasing prevalence of data breaches, phishing attacks, and the ease with which personal information can be obtained from social media platforms by cyber criminals. The what you have category that encompasses device IDs also poses considerable challenges. It is crucial to establish a clear definition of digital identity so that it can be effectively employed to authenticate individuals—even those customers whom financial institutions may not have encountered previously.

Let’s explore three critical shortcomings associated with device ID:

1. Easily Exploited by Cybercriminals: Cybercriminals are continuously adapting their tactics in order to bypass security measures and authentication protocols. When considered independently, device ID becomes vulnerable; criminals have developed multiple strategies for taking control of devices or concealing their use of them.

– Remote Access Tools (RATs): Many fraud prevention systems depend on established parameters related to known devices and IP locations for assessing fraud risk. However, if criminals manage to persuade an unsuspecting legitimate user into downloading a remote access tool—whether it’s a reputable application like TeamViewer or malicious software equipped with RAT capabilities—they can easily navigate around standard device identity checks. These RATs allow attackers complete control over the compromised device while making it seem as though transactions are originating from the legitimate user’s hardware. Consequently, when such tools are active on a system during banking transactions, banks may identify what appears to be an authentic device fingerprint without any indication of proxy usage or anomalies in the IP address and geographical location.

– Social Engineering: In addition to technical exploits like RATs, cybercriminals frequently employ real-time social engineering tactics that manipulate users into revealing sensitive information or performing actions that compromise their security.

In conclusion, while device IDs play an essential role in identifying devices within digital ecosystems as part of broader authentication strategies, they alone cannot provide robust protection against increasingly sophisticated threats posed by cybercriminals who are adept at exploiting these systems.

2: The Challenge of Associating Users with Devices

One of the significant hurdles in establishing a secure connection between users and their devices lies in the inherent difficulty of maintaining consistent user-device relationships. This challenge is compounded by the fact that users frequently transition between different devices. With new models being released regularly, mobile phones often getting misplaced or damaged, and users habitually switching devices, it becomes increasingly challenging to ensure that identity remains fixed and stable over time.

Moreover, many devices are not exclusively owned by one individual; for instance, a family desktop computer in a home office. When such shared devices are employed as authenticators, it creates ambiguity regarding which specific user is engaging with the session on that device. A case in point involves one of our team members who faced authentication issues due to her six-year-old son memorising the passwords: The inability to authenticate new users based on their Device ID poses a significant challenge when it comes to establishing new accounts. This limitation arises because newcomers do not have any prior device history to reference. From the perspective of a financial institution, both a potential fraudster and a legitimate new customer are operating from equally unfamiliar devices. While there may be some merit in identifying confirmed high-risk devices, such instances are rare and do not significantly alter the overall landscape.

Success Stories: Strategies for Comprehensive Fraud Prevention

Despite its limitations, Device ID remains an essential tool in the fight against fraud and should not be discarded entirely. There are numerous fraudulent schemes where Device ID plays a crucial role in detection. However, there exist scenarios where its effectiveness is diminished or non-existent—this is precisely where behavioural biometrics come into play, ensuring that financial institutions can effectively safeguard their operations.

A prominent UK bank recently integrated behavioural biometrics into its mobile banking application. Remarkably, within just days of launching this feature, they were able to uncover multiple attempts at fraud associated with the TeaBot financial malware. This sophisticated threat utilises Remote Access Trojan (RAT) capabilities to commandeer user devices. The behaviour exhibited by malware often diverges significantly from that of genuine users; these distinctive patterns are typically consistent across various types of malware families.

The identification of these anomalies occurs through analysis of user actions such as navigation routes taken within the app, accelerometer readings, and touch or swipe behaviours. Incorporating behavioural biometrics into a multi-layered approach for fraud prevention has yielded encouraging results in recent implementations across several leading banks in the UK—achieving an impressive 1:1 detection rate for identifying malware activity during digital banking sessions.

Furthermore, behavioural biometrics are revolutionising how account opening processes are secured. During this critical phase, factors like typing speed, swipe patterns, and mouse clicks provide insights into whether the user is engaging in legitimate behaviour or attempting fraudulent activity. For instance, data from BioCatch reveals that two-thirds of confirmed cases involving account opening fraud exhibit clear signs indicative of suspicious behaviour rather than genuine usage patterns.

In today’s digital landscape, cybercrime threats are evolving at an alarming rate, necessitating a multifaceted approach to safeguarding businesses and their customers. Imagine a fortress built not just on solid walls but on an intricate network of defences, each layer designed to enhance trust, mitigate risk across various digital platforms, and minimise financial losses due to malicious activities.

At the heart of this strategy lies a combination of behavioural biometrics, device identification, and a myriad of additional data points. These elements are meticulously analysed using sophisticated machine-learning algorithms. For financial institutions and online businesses alike, this comprehensive fraud management framework is akin to constructing a secure haven where customers can engage with confidence.

Examining user behaviour adds an invaluable dimension to our understanding of risk and trust signals. In today’s fast-paced environment, integrating this behavioural analysis is not merely advantageous; it is essential for establishing a robust defence that complements existing device fingerprinting techniques.

Maxthon

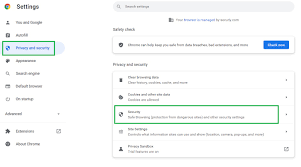

Maxthon has set out on a bold journey aimed at bolstering the security of web applications, fueled by a steadfast commitment to safeguarding users and their confidential data. At the heart of this initiative lies an array of sophisticated encryption protocols, which serve as a robust barrier for information exchanged between users and online services. Every interaction—whether it involves sharing passwords or personal information—is protected within encrypted channels, effectively preventing unauthorised access attempts.

This dedicated emphasis on encryption marks only the beginning of Maxthon’s extensive security approach. Acknowledging that cyber threats continually evolve, Maxthon adopts a forward-thinking attitude toward user protection. The browser is engineered to adapt to new challenges, incorporating regular updates that promptly address any vulnerabilities that may surface.

Users are strongly encouraged to activate automatic updates as an integral part of their cybersecurity practices, ensuring they can effortlessly take advantage of the latest security patches. In this rapidly changing digital environment, Maxthon’s unwavering commitment to ongoing security enhancement not only demonstrates its responsibility toward users but also reflects a deep-seated dedication to building trust in online engagements.

With every update rolled out, users can navigate the web with assurance, confident in the knowledge that their sensitive information is consistently shielded from emerging threats. CES need to be registered within systems, and this process typically hinges on passwords—an element widely regarded as one of the weakest links in cybersecurity protocols.