Analyzing Defense Minister Dong Jun’s Strategic Messaging at the Beijing Xiangshan Forum

At the Beijing Xiangshan Forum on September 18, 2025, Chinese Defense Minister Dong Jun outlined China’s shifting vision for global security and governance. His remarks signaled a strategic pivot in how Beijing seeks to influence the evolving international order.

Dong Jun began by warning against a world governed by the “rule of the jungle,” emphasizing the dangers of unchecked power politics. This phrase alluded to concerns over unilateral actions by major powers, which, according to Dong, threaten global stability. Citing recent conflicts and rising tensions worldwide, he argued that multilateral cooperation is crucial for lasting peace.

In support of this vision, Dong presented China’s military as a “force for peace,” highlighting its participation in United Nations peacekeeping operations and humanitarian missions. According to data from the UN, China is now one of the largest contributors of peacekeeping personnel among permanent Security Council members. This emphasis on international engagement aims to legitimize China’s growing security role.

Dong also framed China’s approach as an alternative to Western-led security models, advocating for equal participation and respect for national sovereignty. Analysts from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace have noted that such rhetoric seeks to position China as a leader of the Global South and a champion of non-interference.

The speech’s strategic dimensions reveal China’s intent to reshape global narratives around power and legitimacy. By promoting its military as peaceful and warning against chaos, Beijing attempts to reassure other nations while expanding its influence.

In conclusion, Dong Jun’s address at the Xiangshan Forum marks a significant development in China’s diplomatic messaging. It reflects a nuanced effort to redefine the global security architecture in ways that advance both Chinese interests and international engagement.

The Rhetorical Architecture of China’s Global Vision

Framing the International System

Dong Jun’s characterization of the current global moment as being “at a crossroads overshadowed by Cold War thinking, hegemony and protectionism” serves multiple strategic purposes. By invoking Cold War imagery, Beijing positions itself as the rational alternative to what it portrays as outdated bipolar thinking. This framing allows China to present its rise not as a challenge to the existing order, but as its natural evolution toward a more equitable system.

The metaphor of the “rule of the jungle” is particularly significant in Chinese diplomatic discourse. It directly challenges Western conceptions of liberal international order by suggesting that current power structures are fundamentally anarchic rather than rules-based. This rhetorical move allows China to delegitimize existing hierarchies while positioning itself as the architect of a more civilized alternative.

The Paradox of Peaceful Military Power

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Dong’s remarks is the assertion that “a strong Chinese military would be a force for peace.” This represents a sophisticated inversion of traditional power politics discourse. Rather than viewing military strength as inherently destabilizing, Beijing frames its military modernization as a stabilizing force that can prevent the very “jungle law” dynamics it criticizes.

This positioning serves several strategic functions. First, it preempts criticism of China’s military buildup by reframing it as a contribution to global stability. Second, it implies that American military dominance has failed to create genuine peace, thus justifying alternative security arrangements. Third, it suggests that China’s military power serves humanitarian and stabilizing purposes rather than narrow national interests.

Singapore’s Strategic Dilemma and Regional Implications

The City-State’s Balancing Act

Singapore’s position in this evolving geopolitical landscape deserves particular attention due to its outsized influence relative to its size. As both a critical node in global trade networks and a trusted neutral venue for international diplomacy, Singapore’s response to China’s messaging carries significant regional weight.

Defense Minister Chan Chun Sing’s historical analogy to World War II is not merely rhetorical flourish but reflects Singapore’s foundational strategic philosophy. Having achieved independence through careful navigation of great power rivalries, Singapore understands intimately the risks that major power competition poses to smaller states. The city-state’s consistent advocacy for multilateralism and institutional solutions stems from this historical experience.

Economic Interdependence and Strategic Autonomy

Singapore faces a particularly acute version of the challenge confronting many regional states: maintaining strategic autonomy while being deeply integrated into both Chinese and American-led economic networks. China represents Singapore’s largest trading partner, while the United States remains crucial for security guarantees and financial services.

This economic reality shapes Singapore’s diplomatic approach to China’s vision for global governance. While the city-state may share some Chinese concerns about unilateral power projection, it cannot afford to alienate either major power. Singapore’s emphasis on rules-based solutions thus serves its national interest in maintaining predictable international frameworks that protect smaller states’ rights.

The ASEAN Dimension

Singapore’s response also has broader implications for ASEAN unity and effectiveness. As one of ASEAN’s most developed members and frequent host to regional summits, Singapore often influences the organization’s collective positions. Its careful balancing between Chinese concerns and established international principles may provide a template for broader ASEAN responses to great power competition.

The challenge for ASEAN lies in maintaining unity while individual member states have varying levels of dependence on China and different threat perceptions. Singapore’s approach suggests that the organization may seek to preserve institutional frameworks while remaining open to evolutionary changes that address legitimate concerns from all major powers.

Impact on Regional Security Architecture

Singapore’s positioning may influence the broader regional security architecture in several ways. First, it demonstrates that middle powers retain agency in shaping great power behavior through institutional engagement and diplomatic positioning. Second, it suggests that regional states may collectively pursue a “third way” that neither fully embraces nor rejects competing visions for international order.

This approach could contribute to the emergence of what might be termed “managed competition” – a framework where great powers compete within agreed institutional boundaries while regional states maintain some influence over the rules of engagement. Singapore’s historical role as a neutral venue and trusted intermediary positions it well to facilitate such arrangements.

Veiled Critique of American Hegemony

Dong’s remarks about “obsession with absolute superiority in military strength” and criticism of external military interference represent barely veiled critiques of American global strategy. By avoiding direct naming, China maintains plausible deniability while making its position clear to international audiences. This approach reflects Beijing’s broader strategy of challenging American hegemony indirectly rather than through confrontational rhetoric.

The timing of these remarks is significant, coming amid what the Reuters report describes as “simmering tension between China and the United States” over multiple flashpoints. Rather than escalating rhetorical tensions, Dong’s approach seeks to position China as the reasonable party advocating for dialogue over confrontation.

The Taiwan Question as Global Order Issue

Dong’s framing of Taiwan’s “return to China” as “an integral part of the postwar international order” represents a particularly sophisticated argumentative strategy. By linking the Taiwan issue to broader questions of international law and postwar settlement, Beijing seeks to transform what many view as a bilateral dispute into a question of global governance legitimacy.

This framing serves multiple purposes. It positions opposition to Chinese claims over Taiwan as opposition to the broader international system established after World War II. It also implies that supporting Taiwan’s autonomy is tantamount to supporting the very “jungle law” dynamics that Dong criticizes. Most importantly, it suggests that resolving the Taiwan question in China’s favor would strengthen rather than undermine international order.

Regional Dynamics and Alliance Building

The Response from Regional Partners

The reactions from Malaysian and Singaporean defense ministers reveal the complex dynamics surrounding China’s vision for regional order. Malaysia’s Mohamed Khaled Nordin’s emphasis on keeping sea lanes “free, open and secure” through international law represents a careful balancing act between Chinese influence and broader international principles.

Singapore’s Chan Chun Sing’s warning about falling into a “vicious cycle” similar to that which led to World War II suggests regional concerns about great power competition regardless of its source. These responses indicate that regional states are not simply accepting China’s framing but are instead advocating for their own vision of stability based on established international law.

Singapore’s Strategic Positioning and Regional Impact

Singapore’s response through Defense Minister Chan Chun Sing carries particular weight due to the city-state’s unique position as both a strategic maritime hub and a balanced regional player. Chan’s historical analogy to World War II is especially significant, as it frames current great power tensions not in terms of ideology or territorial disputes, but as potentially existential threats to the international system itself.

This positioning reflects Singapore’s broader strategic doctrine of “total defense” and its consistent advocacy for multilateral institutions and rules-based order. By echoing Dong’s warning about a divided world while maintaining emphasis on established international frameworks, Singapore demonstrates its signature approach of engaging with rising powers while preserving institutional safeguards.

The impact of Singapore’s stance extends far beyond its physical size. As ASEAN’s most developed economy and a critical financial hub linking East and West, Singapore’s diplomatic positions often serve as bellwethers for broader regional sentiment. Its careful calibration between acknowledging Chinese concerns and maintaining institutional principles suggests that middle powers are seeking to preserve agency in an increasingly polarized environment.

Furthermore, Singapore’s approach highlights the challenges China faces in building regional consensus around its vision for global governance. While Beijing may find sympathy for its critique of current power structures, Singapore’s response suggests that regional states remain committed to evolutionary rather than revolutionary changes to international institutions.

The Challenge of Credible Messaging

The juxtaposition of Dong’s peaceful rhetoric with China’s “large military parade” and display of “new weapons” highlights a fundamental challenge in Beijing’s messaging strategy. While China seeks to position its military growth as stabilizing, the visual demonstration of military capability inevitably raises questions about the peaceful nature of Chinese intentions.

This tension reflects broader challenges in China’s rise. As Beijing seeks to challenge existing power structures while claiming peaceful intentions, it must navigate the inherent suspicion that accompanies rapid military modernization. The effectiveness of China’s messaging depends partly on whether international audiences view its military buildup as defensive or offensive in nature.

Implications for Global Governance

Alternative Models of International Order

Dong’s remarks suggest China’s vision for global governance that differs fundamentally from the current system. Rather than accepting American-led institutional arrangements, Beijing appears to be advocating for what might be termed “harmonious multipolarity” – a system where major powers exercise influence within their respective spheres while avoiding direct confrontation.

This model would presumably allow China greater influence in East Asian affairs while avoiding the zero-sum competition that characterizes current great power relations. However, the viability of such an arrangement depends on whether other major powers, particularly the United States, would accept reduced influence in regions they currently dominate.

The Question of Institutional Change

A crucial question raised by Dong’s remarks concerns the mechanisms through which China envisions global governance transformation. While Beijing criticizes current arrangements, it provides limited detail about specific institutional alternatives. This ambiguity may be strategic, allowing China to maintain flexibility while building broader coalitions around the general principle of reform.

The emphasis on dialogue over confrontation suggests that China prefers evolutionary rather than revolutionary change to international institutions. This approach may prove more palatable to regional partners who benefit from stability but also seek greater voice in global governance.

Strategic Assessment and Future Implications

The Effectiveness of China’s Messaging

The success of China’s rhetorical strategy depends largely on its ability to convince international audiences that its rise represents an opportunity rather than a threat. Dong’s emphasis on peaceful development and critique of “jungle law” politics may resonate with countries that feel marginalized by current power structures.

However, the credibility of this messaging faces several challenges. China’s assertiveness in territorial disputes, its military modernization, and its treatment of domestic dissent all complicate efforts to present itself as a purely peaceful rising power. The gap between rhetorical positioning and observed behavior may limit the effectiveness of Beijing’s diplomatic outreach.

Regional and Global Responses

The measured responses from Malaysian and Singaporean officials suggest that regional states are unlikely to simply accept China’s framing without reservation. Instead, they appear to be advocating for their own version of rules-based order that incorporates both Chinese concerns and broader international principles.

Singapore’s particular emphasis on avoiding the “vicious cycle” that led to global conflict demonstrates how middle powers are attempting to shape great power behavior through historical lessons and institutional frameworks. This approach reflects Singapore’s broader strategy of leveraging its position as a neutral venue and trusted intermediary to promote stability.

The city-state’s response also carries implications for ASEAN unity and the broader Indo-Pacific balance. As a founding member of ASEAN and host to numerous international institutions, Singapore’s diplomatic positioning often influences regional consensus-building. Its careful balance between acknowledging China’s concerns while maintaining commitment to established international law suggests that regional states may pursue a “third way” approach that neither fully embraces nor rejects China’s vision for global governance.

This dynamic suggests that China’s vision for global governance will face significant scrutiny and modification as it encounters the interests and preferences of other states. The ultimate shape of any reformed international system will likely reflect negotiation and compromise rather than unilateral Chinese preferences, with middle powers like Singapore playing crucial mediating roles.

Conclusion

Defense Minister Dong Jun’s remarks at the Beijing Xiangshan Forum represent a sophisticated attempt to reframe debates around global governance, military power, and international legitimacy. By positioning China as the advocate for dialogue over confrontation and rules over “jungle law,” Beijing seeks to transform narratives around its rise from threat to opportunity.

However, the success of this strategy depends on China’s ability to reconcile its rhetorical commitments with its observed behavior in territorial disputes, military modernization, and regional relations. As China continues to challenge existing power structures while claiming peaceful intentions, the international community will likely judge Beijing more by its actions than its words.

The broader implications of Dong’s remarks extend beyond immediate bilateral relations to fundamental questions about the future of global governance. Whether China can successfully promote alternative models of international order while maintaining regional stability remains an open question that will significantly shape global politics in the coming decade.

The Beijing Xiangshan Forum thus serves not merely as a platform for diplomatic messaging but as a window into competing visions of international order. As great power competition intensifies, the ability of major powers to articulate compelling alternatives to current arrangements may prove as important as their military and economic capabilities in determining the future shape of global governance.

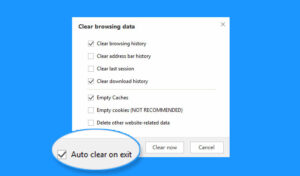

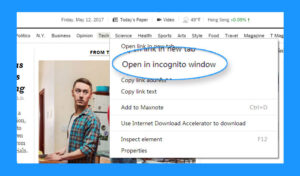

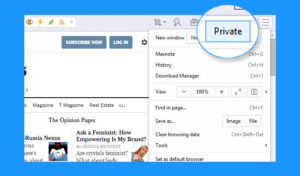

Instructions for Enabling and Disabling Private Browsing Mode in Maxthon Browser

1. Open Maxthon Browser: Launch the Maxthon browser on your device. Ensure you are running the latest version for optimal features and security.

2. Access the Menu: Click on the menu icon located at the top-right corner of the browser window. Three horizontal lines or dots usually represent this.

3. Select Private Browsing: In the dropdown menu, look for the Private Browsing option. Click on it to activate private mode.

4. Confirm Activation: A new window should appear, indicating that you are now in private browsing mode. You may notice a different colour scheme or an icon indicating this status.

5. Browse Privately: While in this mode, your browsing history, cookies, and site data will not be saved once you close the session. Feel free to explore securely.

6. Exit Private Browsing Mode: To return to regular browsing, click again on the menu icon and select Exit Private Browsing from the list of options.

7. Confirm Exit: Once you exit, a message may confirm that you have returned to normal browsing mode.

8. Resume Normal Usage: Continue surfing the internet without any restrictions while your activity is logged as usual again.

9. Check Settings if Needed: If you do not see these options, verify that your browser settings have not turned off private browsing functionality or consult the help section for troubleshooting advice.

Follow these steps carefully to navigate between standard and private modes seamlessly!